Supporting Emerging Visual Artists in Calgary

Supporting Visual Artists to Reach Their Full Potential!

The Calgary Allied Arts Foundation (CAAF) is a not-for-profit organization which has maintained a strong voice for the promotion of arts and culture for many decades. Our mission is to promote the visual arts in Calgary by providing direct support to emerging artists. We do this by supplying studio space, financial aid and mentorship.

CAAF’s residency programs are designed to assist visual artists in advancing their careers and obtaining exhibition opportunities and publicity. CAAF is the only organization in Calgary dedicated to providing studio residencies for visual artists, and many of our previous residents are now successful artists and acknowledge their CAAF Residency as part of their success. We value a diverse, inclusive, and equitable community and commit to creating non-discriminatory residency and exhibition opportunities for artists.

By providing space, mentorship and funding, CAAF is a hub for artists to further explore their creative practice and develop new opportunities.

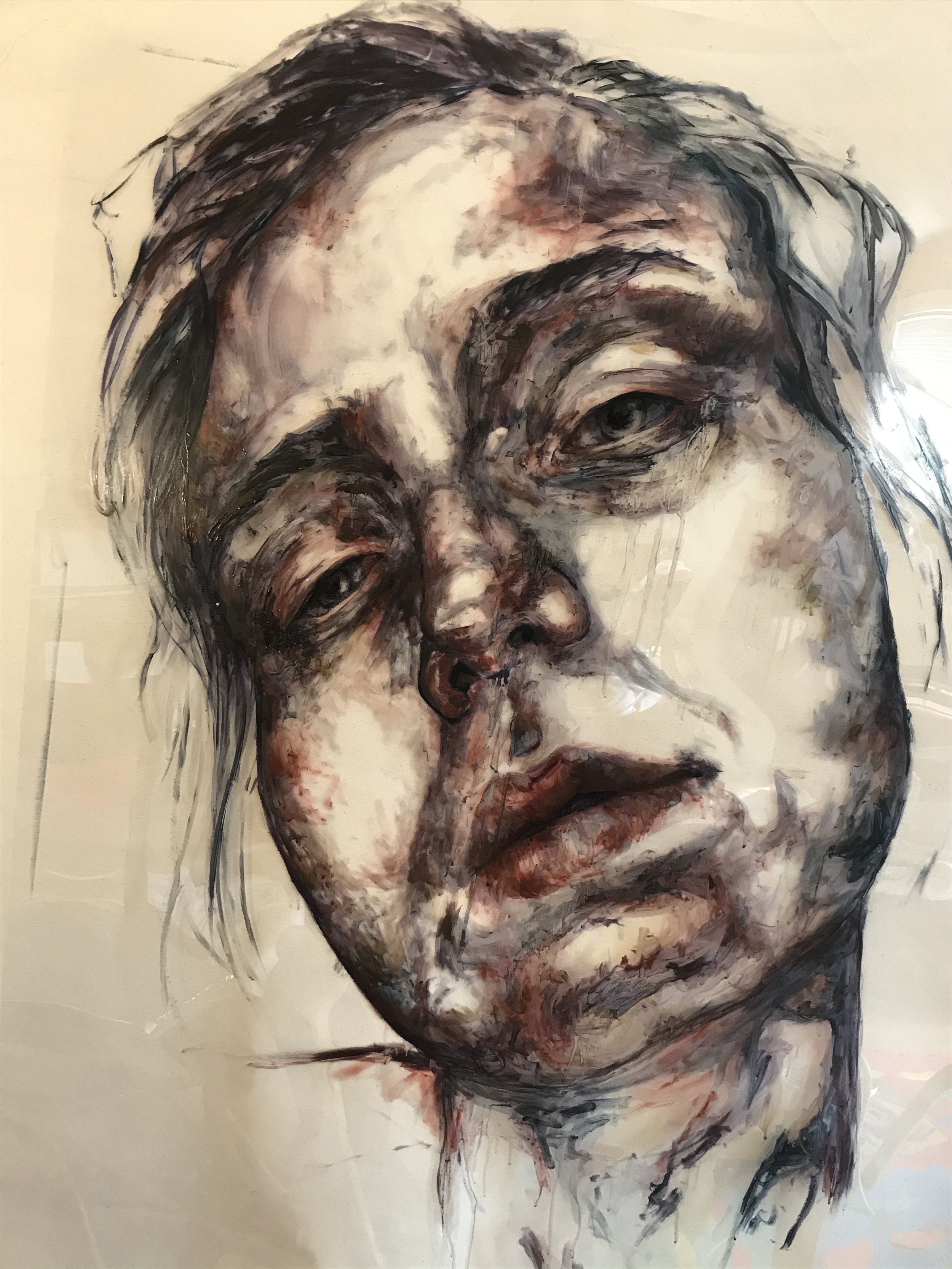

Gallery 505

In addition to CAAF’s multiple residency opportunities each year, through Gallery 505, we provide 3 to 4 previous artist residents solo exhibitions of their work. Gallery 505 is open to the public and accessible to Calgarians working and visiting the downtown core.

Located at 505 8 Ave SW, Calgary, AB.

CAAF’s Window Gallery

Join our Board of Directors!

CAAF is seeking volunteers to join our Board of Directors to help us contribute to the visual arts community in Calgary! We are looking for those with experience in marketing and communications, fundraising and donor stewardship, and more, to fill a few different roles within the board.

We acknowledge the generous support of Calgary Arts Development, the Province of Alberta through Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and our endowment funds at the Calgary Foundation: the Marion and Jim Nicoll Bequest, Douglass Motter Fund, Wesley Irwin Fund and H.B. Hill Trust.

We acknowledge the traditional lands and territories of the Indigenous Peoples who have lived on these lands and taken care of them since time immemorial. We are on Treaty 7 territory, as well as, the historical regional homeland of the Métis, which includes the North Saskatchewan River Territory, the Lesser Slave Lake Territory, and the Lower Athabasca Territory. We acknowledge and respect the histories, languages, and diverse cultures of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit and are grateful for their contributions that continue to enrich our communities.